44 FEET

Sea-Level Rise Risk to a Spent Nuclear Fuel Site on Humboldt Bay

Thirty-seven tons of commercial nuclear waste sit on the inland coast of Humboldt Bay, California in an underground storage facility called the Humboldt Bay Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installation (HB ISFSI). The facility is set into Buhne Point, a highland bluff located northwest of Highway 101 about six miles south of Eureka and directly northeast of King Salmon. The nuclear waste on Buhne Point sits 115 feet east of Humboldt Bay and 44 feet above mean high tide—hence the project title.

Within 44 years, by 2065, Humboldt Bay is projected to experience 3.3 feet (1 meter) of sea-level rise, which will flood the low areas around the ISFSI during king tides, turning it into an island that will be vulnerable to wave erosion and saltwater intrusion, and difficult to access for waste management and relocation. Of particular concern is the potential for an extreme tide, storm surge, or tsunami event to overtop the rock seawall along Buhne Point, rapidly erode the 115-foot shoreline buffer, inundate the HB ISFSI with saltwater, crack the casks and cause radioactive leakage from the ISFSI.

Despite these impending threats to human and environmental health, there is no specific plan for managing the storage facility’s vulnerability to sea-level rise. There is also no permanent disposal site for the 37 tons of spent nuclear waste stored on Humboldt Bay, or for any of the more than 90,000 tons of commercial nuclear waste in the United States.

The aim of this project is to engage community partners and tribal leaders in long-term risk mitigation planning related to the HB ISFSI and sea-level rise. The goals are to share information about sea-level rise science and guide further actions to manage and protect Humboldt Bay’s nuclear waste in a manner that reflects common interests and goals. This website aims to synthesize information on the project’s history and potential futures, and serve as a public hub for the research. Author bios, sources cited, and references are below.

In the future, the project will directly engage diverse participants in a scenario planning exercise that will help decision makers understand the potential outcomes of various decisions under different possible futures.

CONSTRUCTION & OPERATION OF PG&E’S HUMBOLDT BAY POWER PLANT UNIT 3, A NUCLEAR PLANT

The nearly 75,000 pounds (37 tons) of spent nuclear fuel (SNF) (Halpin 2012, p. 32) currently in storage on Buhne Point are waste products from 13 years of electricity production for Humboldt County by Pacific Gas & Electric Company between 1963 and 1976.

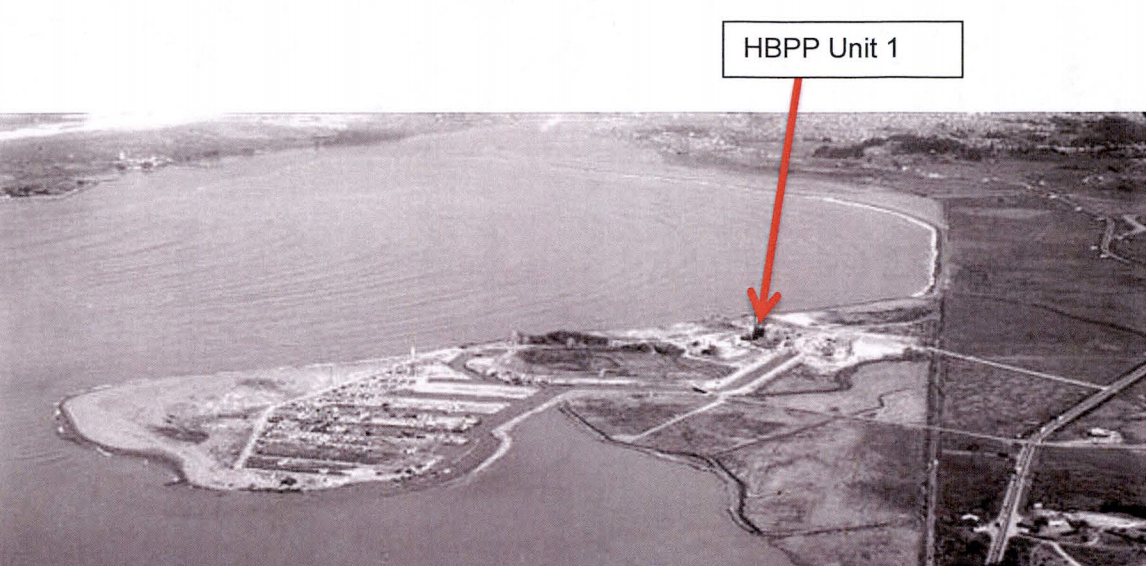

After purchasing 147 acres on the east coast of Humboldt Bay in 1952 (Herbert et al 2012, p. 10), Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) announced in 1958 in the Humboldt Standard, “Atomic Plant Will Be Built Here” (Herbert et al 2012, p. 17), and began building the seventh nuclear power plant in United States on Buhne Point and Red Bluff (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Buhne Point, Red Bluff & King Salmon in the 1950s, following the construction of PG&E’s fossil fuel-powered Humboldt Bay Power Plant (HBPP) Unit 1. (Nuclear Regulatory Commission n.d., p. 4)

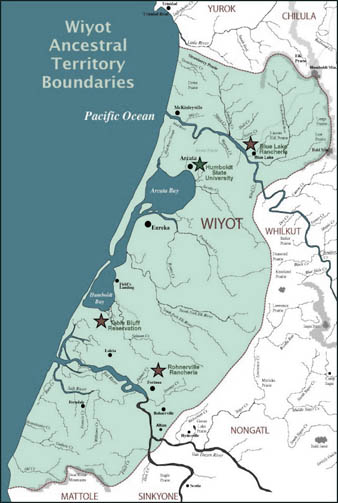

Jurouk Higuchguk is the Wiyot place name for the highland bluff located about six miles south of Jaroujiji (Eureka) on the inland coast of Wigi (Humboldt Bay) where PG&E built its nuclear plant (Canter 2021 Mar, personal communication; Wiyot Tribe 2011).

Jurouk Higuchguk was later renamed Buhne Point—for a Danish ship captain who sailed into Humboldt Bay in 1850 (Find a Grave 2010)—and Red Bluff. Buhne Point and Red Bluff are both now owned by PG&E (Fig. 2), and Buhne Point is designated as the local tsunami evacuation zone for the community of King Salmon.

Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) is a remnant of a historic topographic upland that experienced severe erosion following the construction of jetties at the mouth of Humboldt Bay in the 1890s, and is now located about 2 miles across from the mouth of Humboldt Bay into the Pacific Ocean.

Figure 2. The location of the PG&E property on Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) relative to Humboldt Bay (Wigi), King Salmon and Fields Landing. (Herbert et al 2012, p. 47)

A new nuclear plant on Buhne Point/Red Bluff (Jurouk Higuchguk) allowed PG&E to generate electricity in Humboldt when it was still too remote to affordably import fossil fuels. A growing number of settlers wanted power and enthusiastically supported the local construction of a nuclear plant (McCollum-Martinez 2018, p. 4-7). Messaging from the federal government framed nuclear energy as the future of American innovation, as exemplified in President Eisenhower’s 1953 “Atoms for Peace” initiative (Fig. 3), distracted Humboldt residents from the dangers of building a nuclear plant on the seismically-active, coastal site of Buhne Point/Red Bluff (Jurouk Higuchguk) (McCollum-Martinez 2018, p. 4-7).

Figure 3. A postage stamp promoting Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” initiative. (Wikimedia Commons 2020, “Atoms for Peace”)

PG&E began operating HBPP Unit 3, the 7th nuclear power plant in the United States, in 1963 (Fig. 4) (California Energy Commission 2020, p. 3; Herbert et al 2012, p. 28).

![]()

Figure 4. Humboldt Bay Power Plant sometime after Unit 3 began operating “with the twin 60MW gas-fired generators on the left, and the 63MW nuclear unit on the right.” (Manetas 2020, p. 22)

HBPP Unit 3 was the “‘first privately-owned, constructed, and maintained nuclear power plant in the United States built to provide utility customers with electricity’” (McCollum-Martinez 2018, p. 2), as well as “the first privately-subsidized, sole ownership nuclear facility built in California based on energy demand and projected economic competitiveness with fossil fuel plants, rather than on research and development”

(Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 4). Its economic “success confirmed that nuclear power for commercial use was feasible and triggered further development of similar plants across the nation” (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 4).

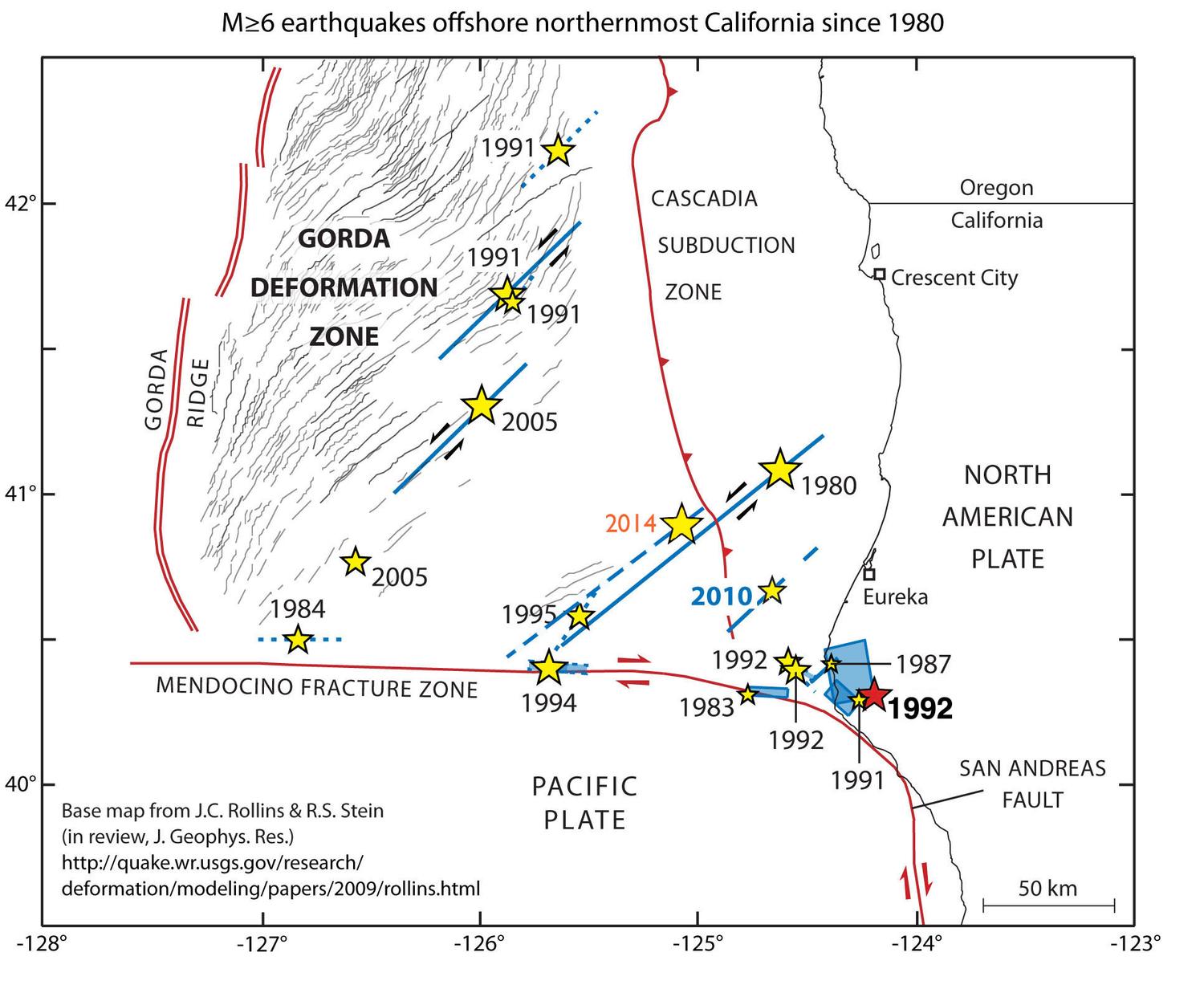

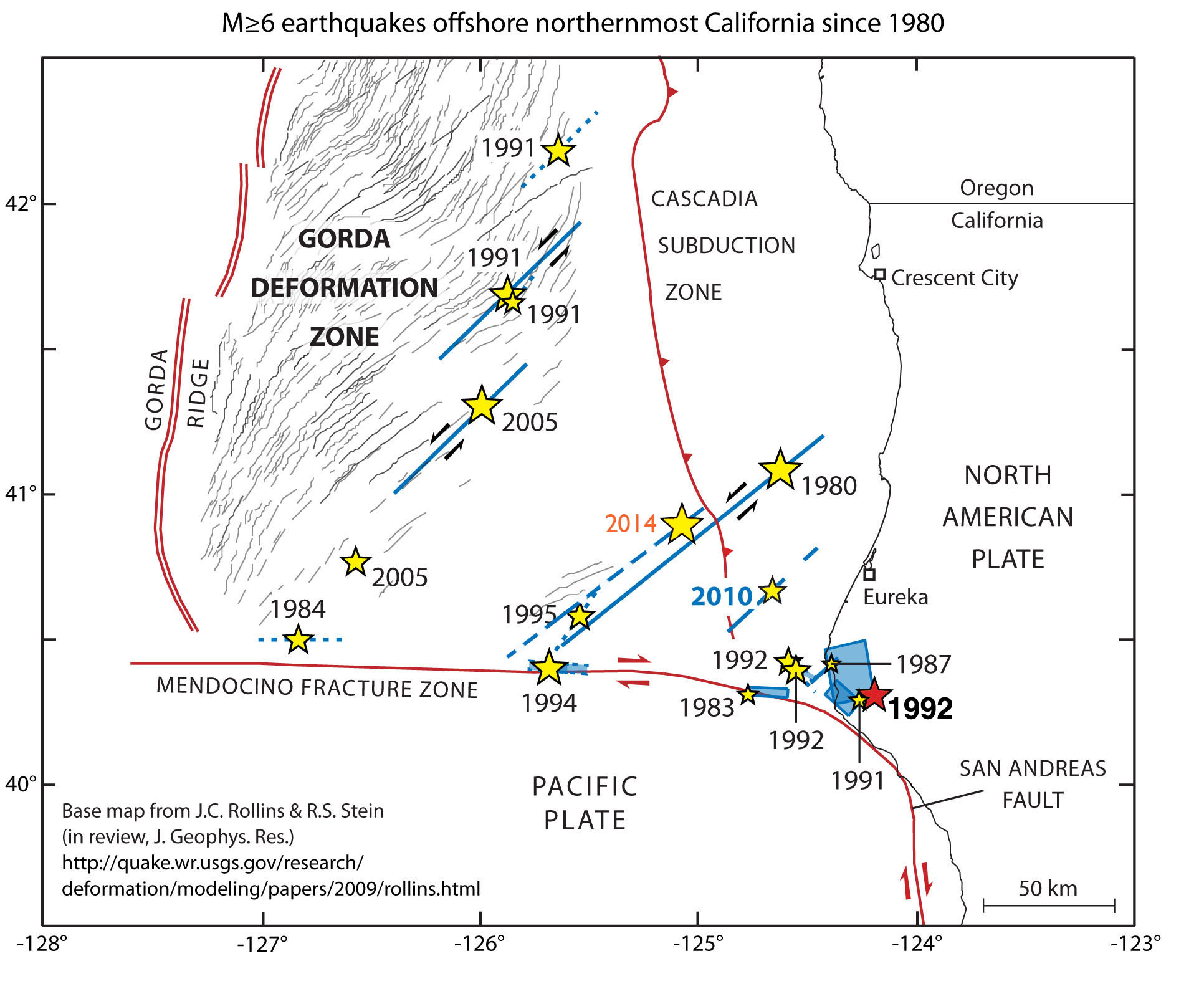

In 1976, after 13 years of operation, PG&E closed down HBPP Unit 3 for routine refueling and a seismic retrofit in response to “new seismic information” about Southern Humboldt Bay (Wigi) (Fig. 5) (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1).

Figure 5. Earthquakes with a magnitude greater than 6 since 1980 near the Mendocino Triple Junction, where the Gorda Plate, North American Plate, and Pacific Plate all meet, creating a seismic hotspot. Note that Eureka (Jaroujiji) is marked by a small black square outline slightly above the red star marked “1992”. (Berkeley Seismology Lab 2017)

Following a loss-of-coolant accident and partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor (Fig. 6) near Middletown, PA, in 1979, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) introduced new safety regulations that necessitated further updates at HBPP Unit 3 (Fortin 2019; Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2018 Jun).

Figure 6. The Three Mile Island nuclear reactor near Middletown, PA, on Susquehannock/Conoy/Ganawese homelands. (Kiner 2019; Middletown Public Library 2021)

Although the HBPP Unit 3 shutdown was originally intended to be temporary, PG&E determined in 1980 “that the cost of completing the required upgrades would make it uneconomical to restart the unit,” and therefore announced plans to decommission Unit 3 in 1983 and “permanently defueled the...reactor in 1984” (Fig. 7) (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1).

Figure 7. The drywell containing the metal reactor vessel, “which was covered in water for shielding as it was remotely segmented for packaging and disposal,” during the decommissioning of HBPP Unit 3. (Manetas 2020, p. 34; Manetas 2021 Mar, email)

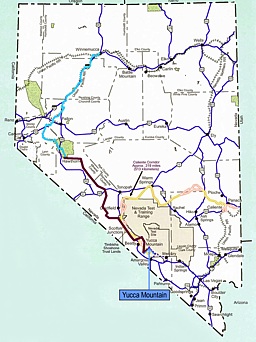

THE NUCLEAR WASTE POLICY ACT: FEDERAL RESPONSIBILITY FOR U.S. COMMERCIAL SNF

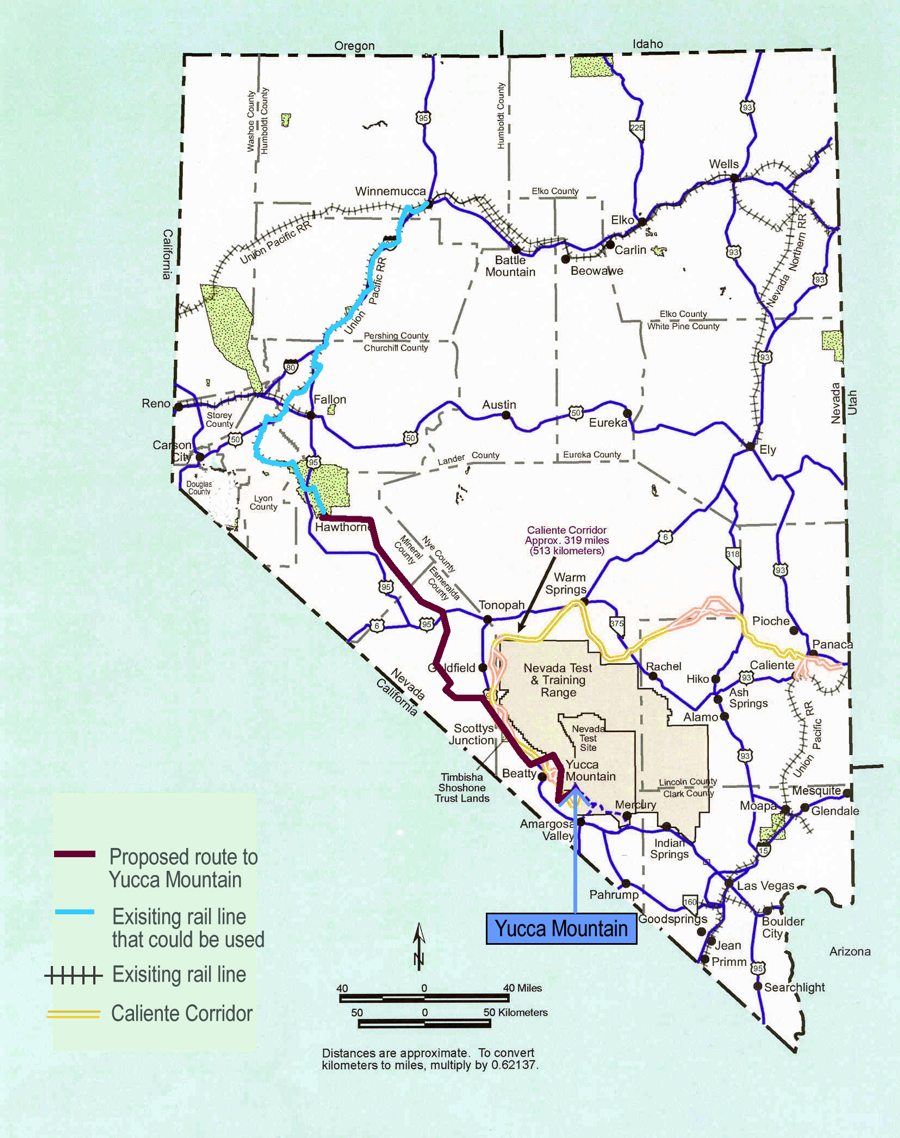

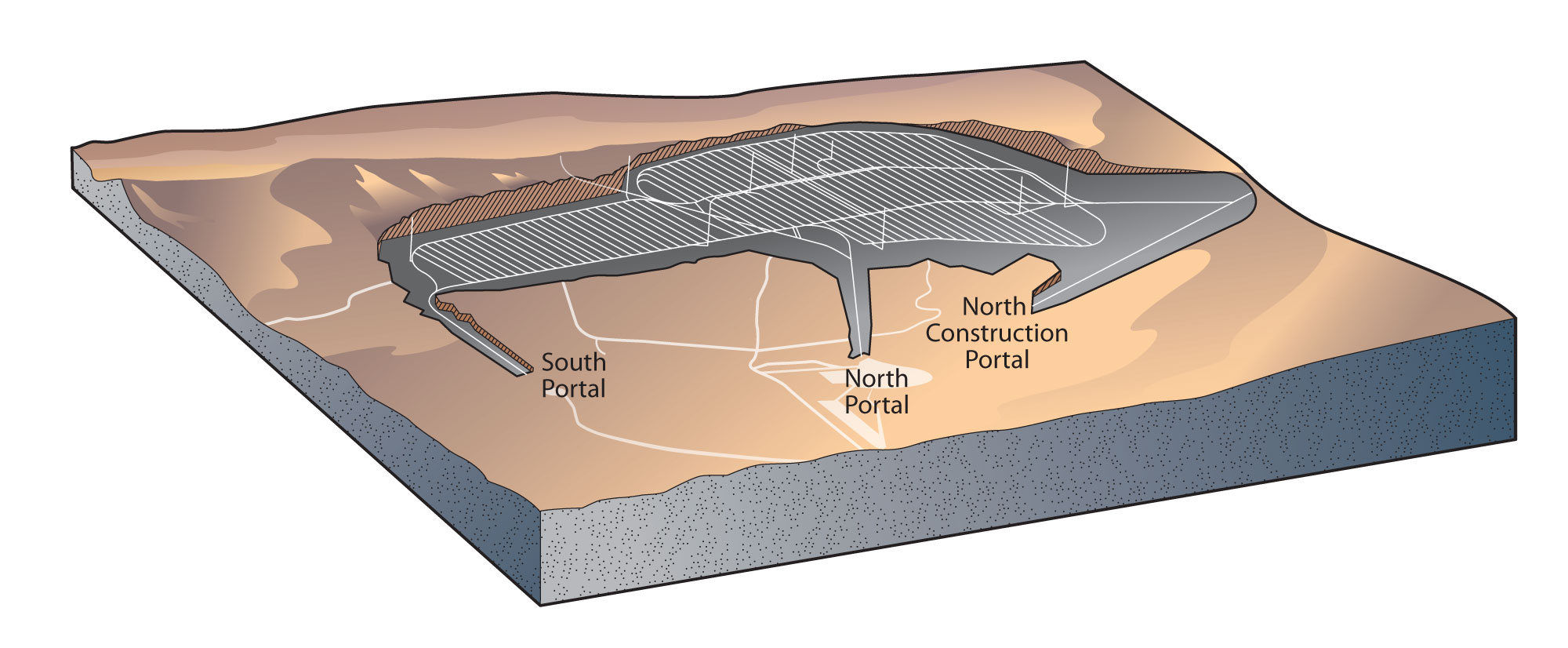

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) of 1982 and amendments from 1987 mandated the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to take ownership and possession of all commercial SNF in the U.S. and permanently dispose of it in a proposed deep geologic repository at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, on Western Shoshone/Timbisha-Shoshone homelands (Nevada’s Indian Territory 2014) (Fig. 8), by the year 1998 (Coplan 2008 May, p. 20; Manetas 2019 Oct; World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar). Therefore, as of 1987, PG&E and other nuclear utilities across the U.S. assumed that the federal government would absolve them of responsibility for their SNF within 12 years.

![]()

Figure 8. The location of Yucca Mountain in SW Nevada, on Western Shoshone/Timbisha-Shoshone homelands (Nevada’s Indian Territory 2014), currently managed by the DOE that also includes the Nevada Test Site for nuclear weapons testing. (Johnson & Walker 2006)

Securely storing and disposing of radioactive commercial nuclear waste is extremely important because “the release of radioactive contamination into the environment is of...potential harm to people and ecosystems from radionuclides...carcinogens [that], at high doses, can also cause rapid sickness and death” (Office of Technology Assessment 1995 Sep, p. 81).

Radioactive materials remain radioactive and dangerous to humans and the environment for 10,000s to billions of years—a nearly inconceivable amount of time that spans numerous human generations, and even civilizations (Coplan 2008 May, p. 3; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2017 Aug 3).

The radioactive isotope uranium-238 (U-238), which makes up about 96% of commercial nuclear fuel and SNF, has a half-life of 4.5 billion years (Pappas 2017). U-235, which makes up the remaining 3–5% of commercial nuclear fuel and SNF, has a half-life of 700 million years (Pappas 2017; Gey et al 2014).

Since “the only way radioactive waste becomes harmless is through decay...[it] must be stored and finally disposed of in a way that provides adequate protection of the public for a very long time” (U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2017 Aug 3). This massive undertaking is a core part of the DOE’s critical role in “ensuring the nation’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges” under the NWPA (DOE Office of Legacy Management n.d.).

DECOMMISSIONING HUMBOLDT BAY POWER PLANT: SPENT FUEL POOL STORAGE

In 1988, the NRC approved PG&E’s decommissioning plan for HBPP Unit 3 and revised their operating license to a possess-but-not-operate license (SAFSTOR status) set to expire in 2015 (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 40; Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1).

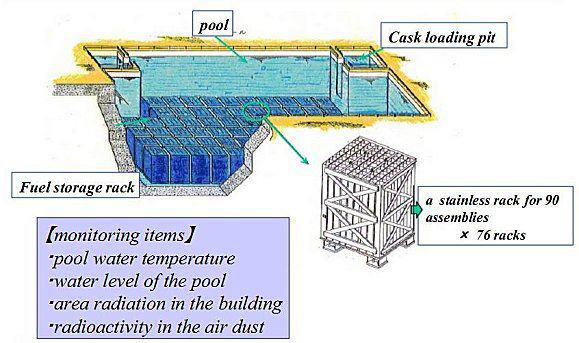

PG&E designed and implemented an on-site spent fuel pool (SFP) (Fig. 9) at HBPP to begin meeting its decommissioning requirements. SFPs as an innovative method for storing fresh, highly radioactive SNF in wet storage “set a national precedent and was emulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission” and “at least 14 other decommissioned plants across the United States” by 2003 (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 4).

Figure 9. A diagram of a generic spent fuel pool (SFP) including the pool of water, a cask loading pit, and an array of stainless steel storage racks for SNF assemblies. (Livingston 2012)

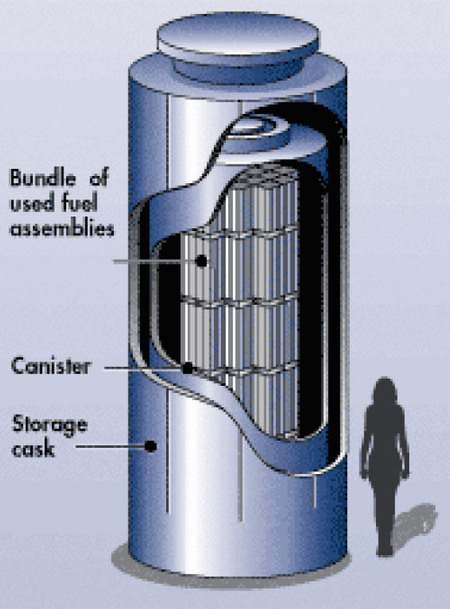

In an SFP, SNF pellets are bundled into assemblies (Fig. 10) and stored on racks submerged in 20–40 feet of water (Union of Concerned Scientists 2012). Similar to its purpose in an operating nuclear reactor, the water provides “shielding from the radiation for anyone near the pool” and allows the SNF to decay until it is safe enough to transfer into dry storage without cooling water as radiation shielding—usually about 5 years (U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2020 Jul 8).

Figure 10. The SNF assemblies from HBPP Unit 3 in on-site wet storage in the SFP on Buhne Point. (Manetas 2020, p. 27)

DELAYS TO YUCCA MOUNTAIN

Despite its legal obligation under the NWPA to provide permanent storage for all commercial SNF in the U.S. by 1998, the DOE (Fig. 11) announced in 1989 that “technical and institutional complexities of site characterization make it unlikely that a repository [at Yucca Mountain] would be available before 2010” (Dunster 2017-2018).

The DOE therefore began paying nuclear utilities more than $2 million a day to continue storing their SNF at the respective nuclear plant sites—notably, “that’s taxpayer money.” (Klaus 2020; Rott 2019 Apr). This practice has continued for more than 30 years, and will persist until the government fulfills its responsibility for the nuclear waste. As of March 2021, “California electricity users once served by the nuclear plant have already paid nearly $1 billion into the federal Nuclear Waste Fund, which now totals more than $43 billion” (Dobken 2021 Mar).

Figure 11. Department of Energy headquarters at the Forrestal Building in Washington, D.C. (Kruger 2013)

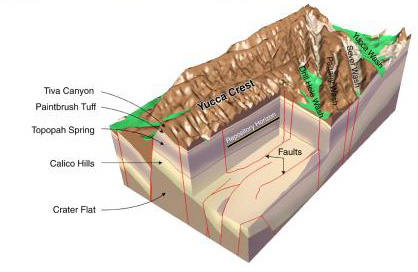

One major reason for the DOE’s delay was scientific research that suggested the proposed YMDGR site may be wetter than initially believed. One assumption of design for the TMDGR was a very dry environment, so more moisture than expected could lead to stress corrosion cracking (SCC) (Fig. 12) of the steel dry storage casks—even despite all of the “corrosion-resistant” materials engineering (Dunster 2017-2018; Xie & Zhang 2015). Cracks in the dry storage casks containing nuclear waste are a major mechanism by which radioactive leakage can occur.

In particular, researchers expressed concerns that an earthquake at Yucca Mountain (Fig. 13) could raise the groundwater table beneath the repository, flood the repository from below, degrade the dry casks, and thus enable radioactive waste to leak into the environment (Krotz 2002; State of Nevada Nuclear Waste Project Office 1999).

Figure 13. A graphic of Yucca Mountain and Crest, with the black line as theproposed repository horizon and the red lines as local earthquake faults. (Krotz 2002)

For PG&E and other nuclear utilities storing commercial SNF on-site at decommissioned power plants, this DOE announcement delayed the promise of federal acceptance and disposal of any SNF by at least 12 years.

This additional delay was not a trivial development for nuclear utilities that had already been managing nuclear waste for a decade or more in SFPs designed to temporarily store SNF for only about 5 years (Jorgustin 2014; Union of Concerned Scientists 2013 Oct).

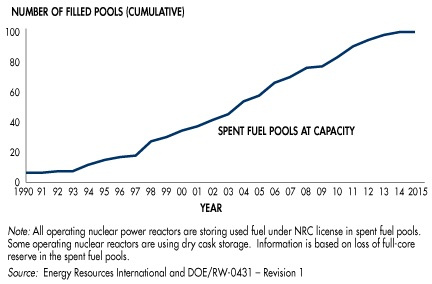

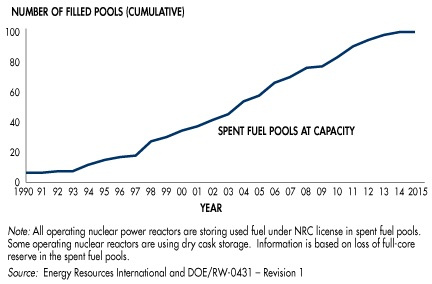

In addition, throughout the early 1990s, SFPs across the U.S. began reaching capacity (Fig. 14), generally full of SNF safe enough to be transferred into dry storage but with nowhere to go.

Figure 14. The number of cumulative SFPs filled to capacity in the U.S. between 1990 and 2015. (Beyond Nuclear 2011)

With a deferred timeframe for federal acceptance of SNF and fuel reprocessing commercially unavailable in the U.S. (California Energy Commission 2020, p. 1), in the 1980s and 1990s, PG&E and other U.S. nuclear utilities began turning to on-site dry cask storage as an alternative, albeit still temporary, solution for the SNF stored in SFPs at their reactor sites

(U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2019 Dec).

Figure 15. The nuclear fuel and waste cycle; commercial SNF in the U.S. is stuck on the purple “Storage” step. (World Nuclear Association 2020 Sep, “Nuclear Fuel and its Fabrication”)

DECOMMISSIONING HUMBOLDT BAY POWER PLANT: DRY CASK STORAGE

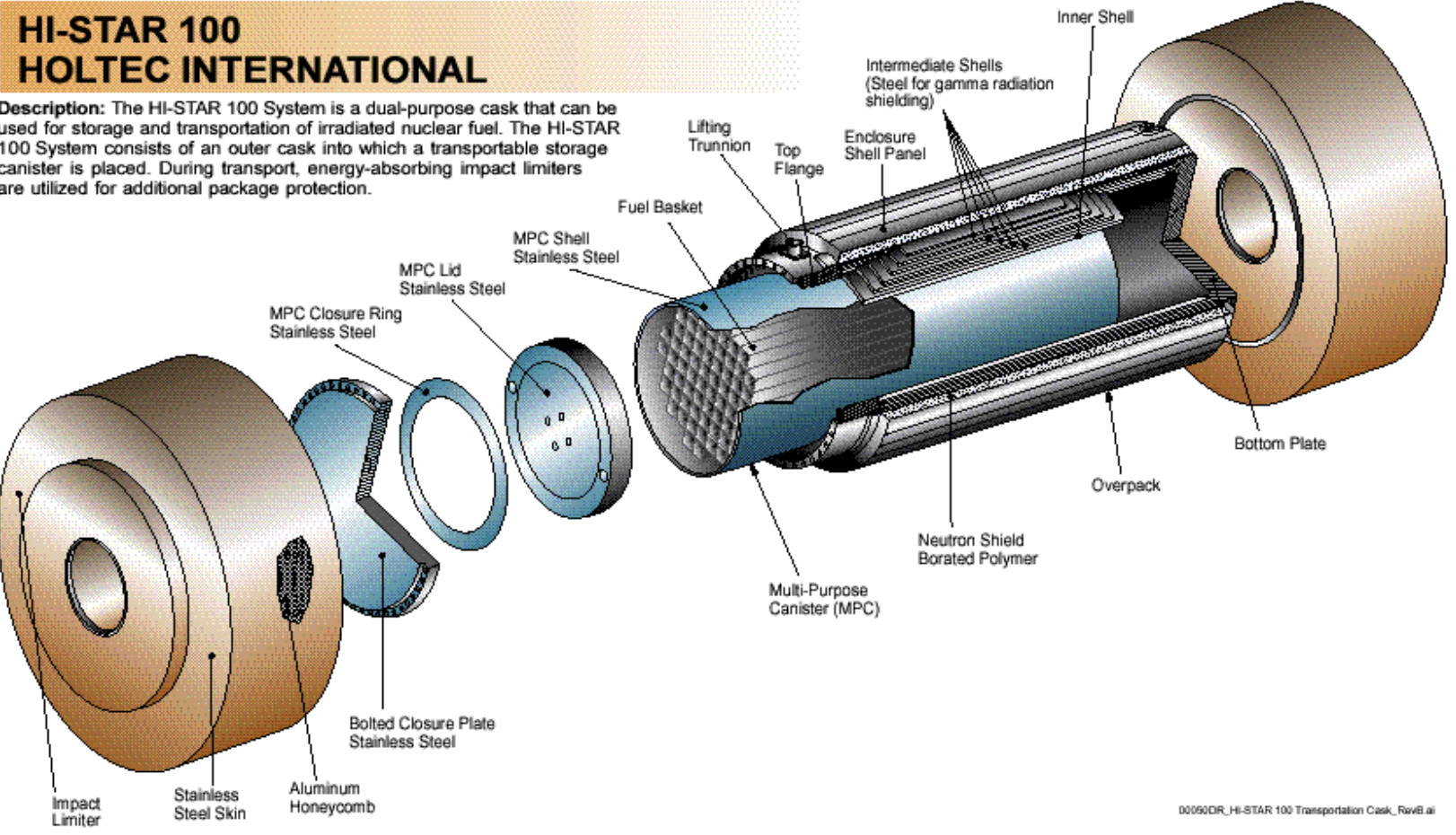

Throughout the 1990s, PG&E worked with the energy technology company Holtec International to develop the Holtec International Storage, Transport and Repository System for Humboldt Bay (HI-STAR HB), an on-site dry cask storage system for the SNF from HBPP Unit 3 currently in wet storage on Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) (Holtec International 2010, p. 40).

The multi-purpose canister (MPC) for the storage and transport of SNF in HI-STAR HB is a smaller version of Holtec’s original HI-STAR 100 MPC (Fig. 16) that is “specifically designed for Humboldt Bay fuel” (Holtec International 2010, p. 31).

Figure 16. Holtec’s original HI-STAR 100 dual-purpose cask “that can be used for the storage and transportation of irradiated nuclear fuel.” An outer cask, or overpack, encases the storage canister that contains the spent fuel assemblies, and impact limiters on either end of the cask provide “additional package protection.” (Jones 2006, p. 5)

While equal in outer diameter and thickness to the original HI-STAR 100 MPC (Fig. 17), HB MPCs are “approximately 6.3 feet shorter than the generic...design” at about 10 feet tall (Fig. 18) (Holtec International 2010, p. 40). Each HB MPC “can contain up to 80 fuel assemblies” (Holtec International 2010, p. 40).

Figure 17. A generic upright dry storage cask, MPC and bundle of used fuel assemblies with a human figure for size comparison. (U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2017, “Typical Dry Cask Storage System”)

Figure 18. One of the 6 HI-STAR HB dry casks before it was loaded with SNF and stored underground. (Manetas 2020, p. 29)

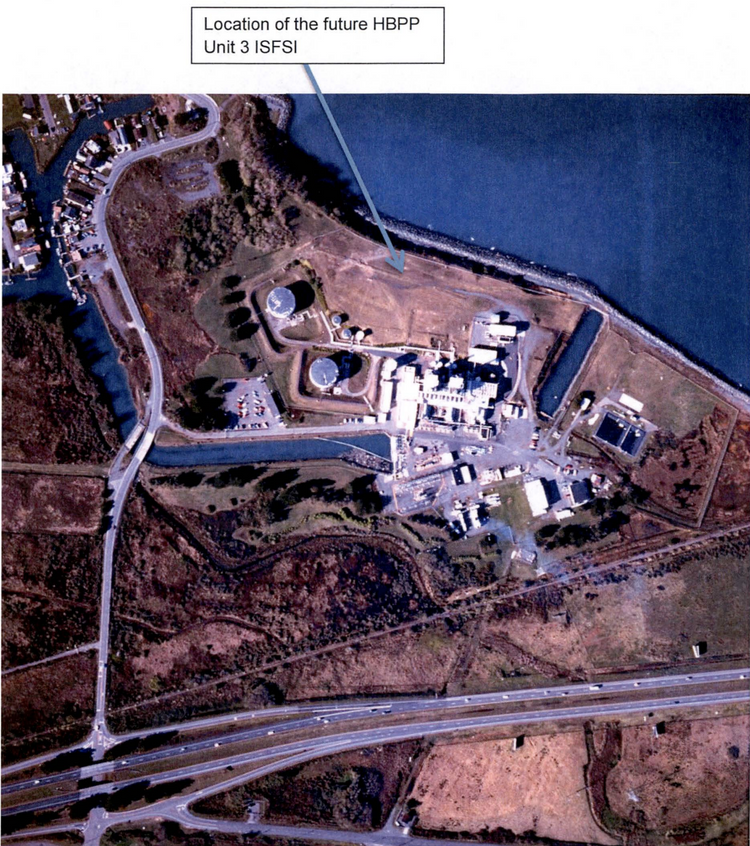

In 2005, the NRC issued PG&E a site-specific license to implement the HI-STAR HB at the Humboldt Bay Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installation (HB ISFSI) on Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) and operate it for 20 years until 2025 (Fig. 19) (Benner 2005, p. 1; Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2017 Nov, p. 16).

Figure 19. The location of the future HB ISFSI on Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) in the early 2000s, as indicated by the gray arrow. (U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission n.d., p. 9)

The HB ISFSI and its associated infrastructure was constructed on Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) adjacent to PG&E’s partially-decommissioned HBPP on Red Bluff in 2007 (Ch2m Hill Engineers 2015, p. 16). The entire HB ISFSI site covers slightly more than 11,000 square feet (Fig. 20), and sits at 44 feet above sea level (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 6).

Figure 20. An aerial view of the modern HB ISFSI showing the vault structure, access roads, security buildings and fenced perimeter. (Manetas 2020, p. 70)

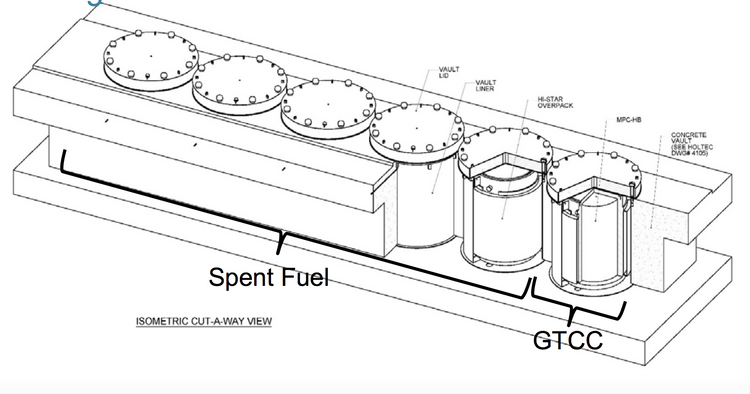

In 2008, six casks of nuclear waste from HBPP Unit 3 were moved from wet storage in SFPs into dry storage in the underground HB ISFSI on Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk), where they remain to this day. Five casks contain SNF and the sixth contains other high-level, Greater Than Class C (GTCC) waste (Fig. 21).

(Ch2m Hill Engineers 2015, p. 16)

“There are 390 fuel assemblies in the HBPP inventory, and a quantity of loose

debris that could constitute an equivalent of one additional assembly. Each fuel

assembly contains approximately 192 pounds (87 kg) of UO2 [uranium dioxide]” (Halpin 2012, p. 32). Therefore, the HB ISFSI contains 37.44 tons (74,880 pounds) of radioactive uranium dioxide.

Figure 21. An isometric cutaway view of the 6 dry casks in the HB ISFSI, with five that contain SNF and one with other GTCC waste. The diagram points out the casks’ vault lids, vault liners, HI-STAR overpacks, MPC-HBs, and concrete vault structure. (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2017 Dec, p. 7)

The HB ISFSI is set 115 feet back from the modern edge of Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) (Fig. 22) and about 15 feet into the ground, such that the tops of the casks are visible a few feet above the ground at about 47 feet above sea level and the bottoms of the casks sit beneath the surface at 20–30 feet above sea level (Holtec International 2010, p. 40; Page 2005, p. 7).

Figure 22. An aerial view of the modern HB ISFSI on Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk), with a red arrow showing the 115 feet between the vault structure and Humboldt Bay (Wigi). (Laird 2019, p. 26)

SEA-LEVEL RISE ON HUMBOLDT BAY

The southeastern coast of Humboldt Bay (Wigi), including Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk), is buffered from wave-induced erosion from by a protective rock seawall built in the 1950s (Fig. 23 & 24) to prevent land loss as seen in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

![]()

Figure 23. The seawall along Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) in 2020. (Abigail Lowell 2020 Dec)

![]()

Figure 24. The coast of Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk), 70 years ago, in 1952. (Lloyd Stine 1952)

Figure 24. The coast of Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk), 70 years ago, in 1952. (Lloyd Stine 1952)

Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) currently lies at 44 feet above mean sea level, but, notably, the surrounding landscape is much lower. For example, King Salmon and Red Bluff (Fig. 25) have elevations of 3 feet above sea level.

Figure 25. Map of King Salmon, Buhne Point, and Red Bluff (Jurouk Higuchguk) on the southeast coast of the Humboldt Bay (Wigi). (TopoQuest 2008)

Between 1870 and 1970, spanning the construction of jetties at the mouth of Humboldt Bay

by the Army Corps of Engineers

in the 1890s that intensified wave action in the bay, and the placement of Buhne Point’s protective seawall in the 1950s, Buhne Point/Red Bluff (Jurouk Higuchguk) eroded 1,480 feet (0.28 miles or 451 meters), or almost 15 feet per year (Fig. 26) (Laird 2019 Nov, p. 11; Page 2005; Walters 2013).

![]()

Figure 26. “Overlay of erosion of Buhne Hill and shoreline, pre-jetty (1870 shoreline) and post-jetty construction (1940, 1970, and 2017 aerial photographs).” The black arrow indicating 1,480 feet of erosion in 100 years also happens to point to PG&E’s property on Buhne Point/Red Bluff (Jurouk Higuchguk). (Laird 2019 Nov, p. 25)

The seawall along Buhne Point and Red Bluff (Jurouk Higuchguk) has served its purpose well for the past 70 years. However, projected sea-level rise (SLR) in Humboldt Bay (Wigi) in the coming decades associated with global climate change could render the seawall ineffective and reintroduce historic rates of land loss to Buhne Point and Red Bluff (Jurouk Higuchguk). Humboldt Bay (Wigi) is projected to experience 3.3 feet (1 meter) of SLR as early as 2065 under the high-risk climate change scenario (California Ocean Protection Council 2018; Laird 2019 Nov, p. 29).

With two meters of sea level rise in Humboldt Bay, monthly and annual high tides could overtop the protective revetment wall protecting the bluff. Based on Ocean Protection Council’s 2018 sea level rise projections, two meters of sea level rise could occur “as early as 2076 under the extreme scenario, or by 2093 under the high-risk projection” (Laird 2019). This projection is also supported by the California Coastal Commission’s current sea level rise principles for aligned state action (California Coastal Commission 2020, p. 4). Although Principle One reinforces using the high-risk aversion projection as the more protective target for critical infrastructure such as the ISFSI, the extreme projection of around 2076 for 2.0 meters of sea level rise would be the most protective for an exposed site such as Buhne Hill.

Without mitigative or adaptive action in the next 40 years to protect the HB ISFSI or move the SNF elsewhere, SLR in Humboldt Bay (Wigi) will effectively turn the HB ISFSI into an island by flooding “King Salmon Avenue, PG&E’s Humboldt Bay Generating Station, former HBPP, 2 access roads, and a portion of the sea wall on Humboldt Bay during MAMW [mean annual maximum water] or king tides” (Fig. 26) (Laird 2019 Nov, p. 29; MacPherson 2019). According to sea-level rise expert and Humboldt Citizens Advisory Board member Aldaron Laird, “MHHW [mean higher high water] would overtop (daily) the seawall and make Buhne Point an island with 2.0 meters of SLR, MMMW [mean monthly maximum water] (monthly = chronic flooding) would do this with just 1.5 meters of SLR, and MAMW [mean annual maximum water] (king tides = nuisance flooding) with 1.0 meter of SLR (Fig. 27) (Kalt 2021; Laird 2021 Apr, email; NOAA n.d.). Laird questions whether, after decommissioning HBPP, “PG&E will have any interest in [the Buhne Point] property given that access and its power generating facilities will be inundated” (Laird 2020 Jun, email).

Figure 27. A diagram showing mean higher high water (MHHW), mean high water (MHW), mean sea level (MSL), mean low water (MLW), and mean lower low water (MLLW). (Kalt 2021, from the COMET Program)

Tidal inundation directly around Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) would also reintroduce severe wave-induced erosion to the bluff and gradually work away at the present 115 feet of earth between the nuclear waste and the edge of the bluff. Wave erosion and land loss at Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk) could expose the HB ISFSI to periodic saltwater inundation during high tide events. Saltwater inundation can cause chlorine-induced stress corrosion cracking (CISCC) in stainless steel storage casks, which is a mechanism for radioactive leakage from ISFSIs. Therefore, of particular concern is the potential for radioactive leakage from the ISFSI if its 115-foot shoreline buffer rapidly erodes (Fig. 28) during a high tide, storm surge, or tsunami event that overtops the rock seawall around Buhne Point (Jurouk Higuchguk).

Figure 28. An example of coastal land loss and infrastructure damage from wave erosion. (Dronen 2018)

Dry casks have a design life of 20–40 years, according to NRC regulations (Coplan 2008, p. 12; Marlow 2020, p. 39). In June 2020, the NRC extended PG&E’s original 20-year operating license for the HB ISFSI by an additional 40 years. The HB ISFSI is now licensed for a total of 60 years, until 2065—the same year that one meter of SLR is projected for Humboldt Bay. According to Mike Manetas, long-time member of the Humboldt Bay Power Plant Citizens’ Advisory Board (HBPP CAB), “the re-licensing of the ISFSI was...bulldozed through both the CAB and the general public. There was no public hearing or comment period...it just happened” (Manetas 2021 Mar, email).

There is no plan for managing the HB ISFSI’s vulnerability to sea-level rise, and “just as importantly, there is no emergency plan to respond to and deal with any kind of accident or incident now or in the near future. Since the spent fuel pool, which cooled and shielded the fuel is gone, any compromise of the casks [in the HB ISFSI] potentially exposes the public, as well as workers, the bay, and the environment in general to release of radiation” (Manetas 2021 Mar, email). Also, as of now, after more than 70 years of effort in the U.S., there is no determined alternative location for the 37 tons of nuclear waste on Wigi (Humboldt Bay), nor for the 900,000 tons of nuclear waste stored across the entire U.S.

CONTINUED CONTROVERSY OVER U.S. NATIONAL NUCLEAR WASTE DISPOSAL AT YUCCA MOUNTAIN

In June 2008, the DOE presented its license application for YMDGR to the NRC (Fig. 30) (Klaus 2020).

Figure 30. Energy Department representatives presented the Yucca Mountain license application to the NRC. (Klaus 2020)

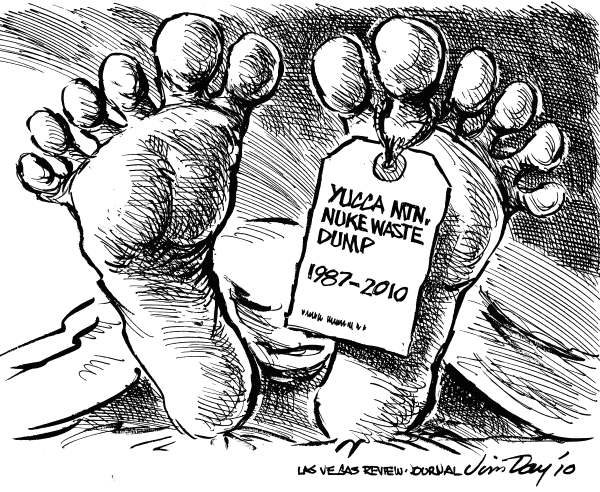

In 2010, the Obama administration tried to eliminate funding from the Yucca Mountain project and “withdraw the [NRC] license application” for the proposed YMDGR (Fig. 31), fulfilling promises Obama made while campaigning in Nevada before his election in 2008 (Mascaro 2010).

Figure 31. “The Yucca Dump Zombie...Be sure to count the toes! They have been seen to twitch from time to time, since Trump took office.” (Beyond Nuclear 2018, cartoon by Jim Day in 2010 for the Las Vegas Review Journal)

However, the NRC rejected the DOE’s motion to withdraw the YMDGR license application, and in August 2013 the U.S. Court of Appeals ordered the NRC to resume reviewing the DOE’s license application for YMDGR, so the process continued (World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar).

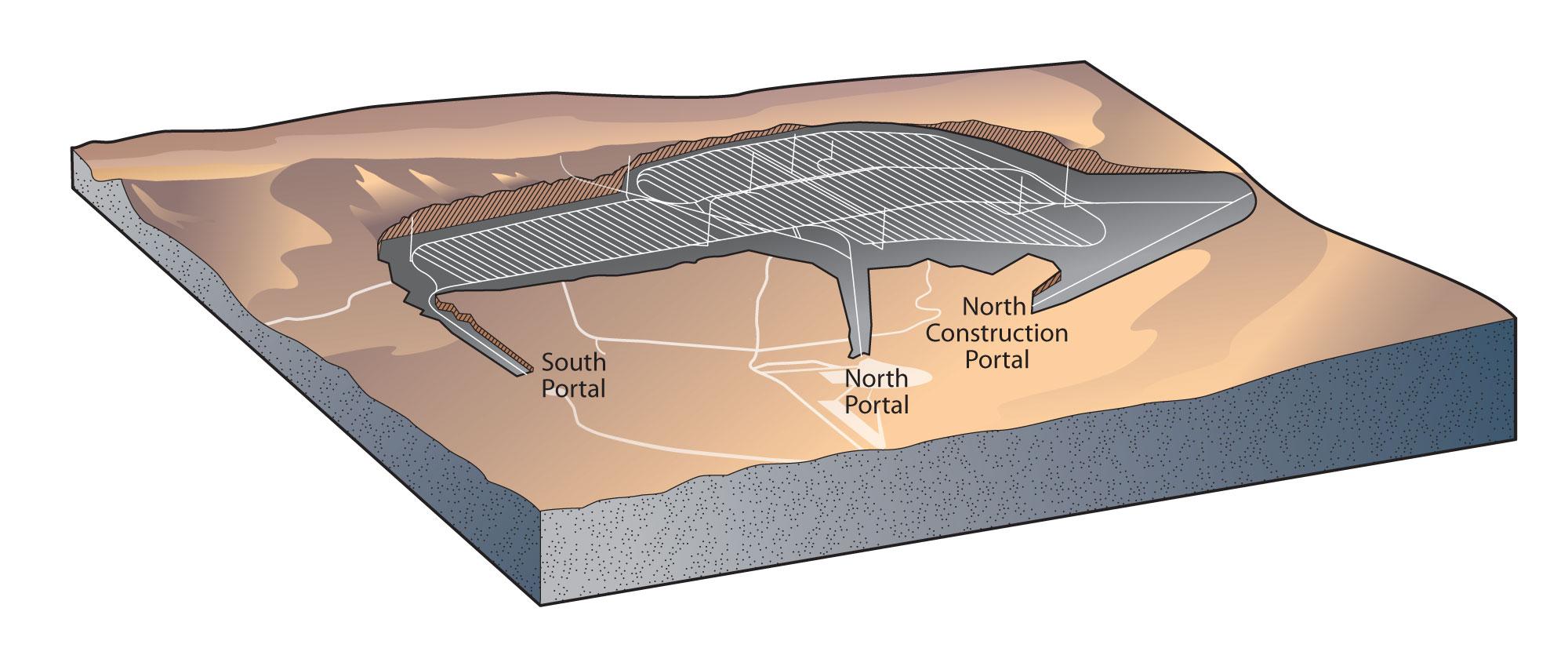

The NRC’s final safety evaluation report, final technical safety review, and final supplement to the DOE’s Environmental Impact Statement for YMDGR (Figs. 32 & 33) from 2015 and 2016 all “established that the repository design would prove safe for 1 million years” (World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar).

Figure 32. Aerial view of YMDGR site, located on Sioux/Cherokee/Iroquois homelands. (American Indian 2021; Yucca Mountain Project 2017)

Figure 33. Schematic diagram of YMDGR site, located on Sioux/Cherokee/Iroquois homelands. (American Indian 2021; Wikimedia Commons 2008)

These results were especially notable in the context of new NRC safety regulations for nuclear power plants and storage sites following the 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan (Fig. 34) (U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2019 Dec) Regulatory Commission 2019 Dec).

Figure 34. The 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan. Damage caused by offshore earthquake on March 11, 2011 (© DigitalGlobe).

However, “Nevadans who balk at burying waste in their own backyard—and outsiders who want to be in their good graces—argue the mountain’s rock is too volcanic and earthquake-prone to suit such long-term storage” (Fig. 35) (Grandoni 2020).

In 2015, the Obama administration determined that repositories for defense-related and commercial nuclear waste should be constructed and operated separately because the “DOE reported that defense waste is smaller in volume, less radioactive, and thermally cooler than commercial spent nuclear fuel,” such that “a defense repository may be easier to develop” (U.S. Government Accountability Office n.d.).

This decision defied the NRC’s plans for storing combined nuclear waste storage at YMDGR (Fig. 36), and further delayed the development of a federal permanent repository for SNF at Yucca Mountain.

In 2016 and 2017, the Trump administration’s fiscal year budgets for 2017 and 2018 respectively “included $120 million for the resumption of the license review for the repository at Yucca Mountain,” but Congress did not provide funding in either year (U.S. Government Accountability Office n.d.).

As of March 2019, PG&E plans that the DOE will transfer the SNF away from HB ISFSI between 2031 and 2033 (Welsch 2019, p. 32). If the federal government meets this third deadline under the NWPA, it would amount to a 35-year delay in taking responsibility for U.S. commercial SNF. However, continued political contention over the project does not bode well for its future success.

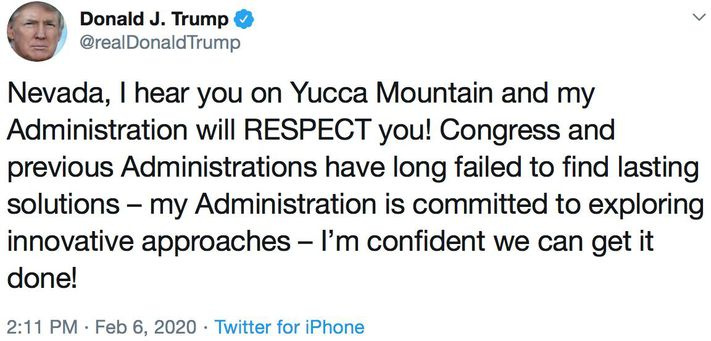

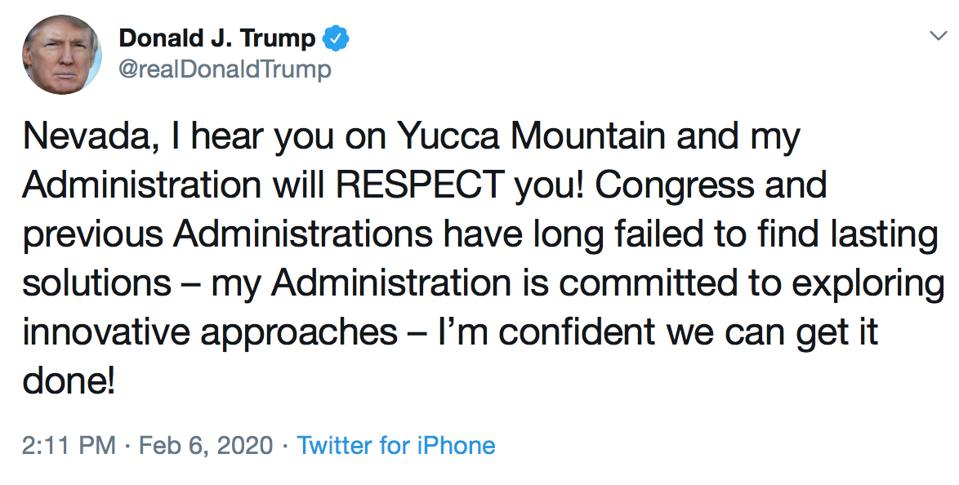

The Trump administration’s 2021 fiscal year budget proposal from February 2020 did “not include funding for licensing of Yucca Mountain as a nuclear waste repository,” which marked “an abrupt reversal of [the] administration’s policy” after three years of supporting the project (Hulac 2020).

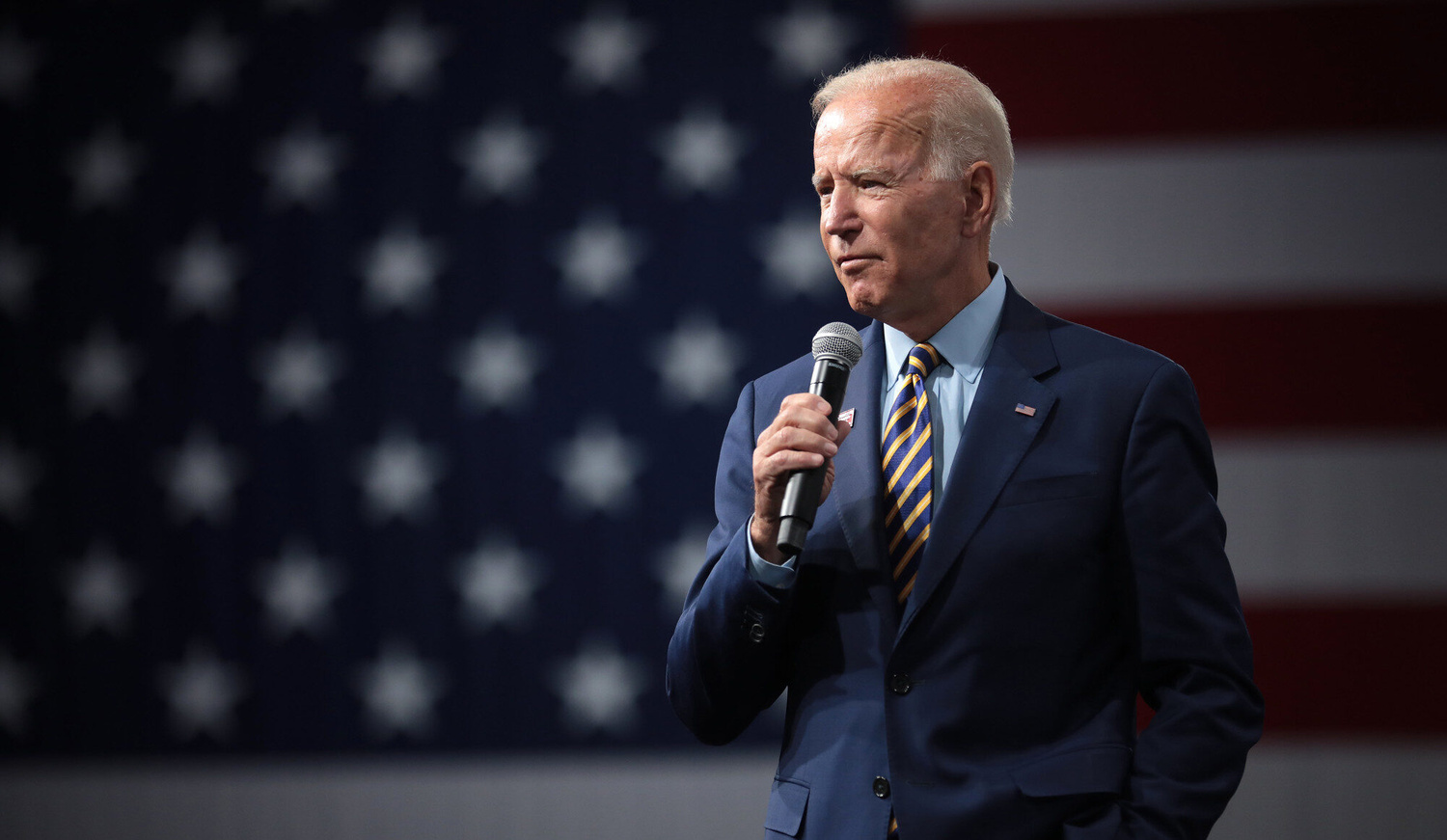

In response to Trump, then-presidential candidate Joe Biden expressed his disapproval for the contradiction between Trump’s funding allowances for YMDGR and what he called “empty promises on Twitter,” referring to a Tweet from Trump in February 2020 (Fig. 37) (Gartner 2020; Grandoni 2020).

Figure 37. Tweet from Trump in February 2020 expressing his support of Nevadans opposed to YMDGR. (Conca 2020)

Biden (Fig. 38) stated that “under a Biden administration there would be absolutely zero dumping of nuclear waste in Nevada” (Gartner 2020; Grandoni 2020). Instead, he “wants to establish a new agency to incubate technology startups and other projects that look into the issue of nuclear waste storage” in support of the Green New Deal (Grandoni & Stein 2019).

Figure 38. President Joe Biden discussing his administration’s Clean Energy Plan. (Marcus 2021)

Biden’s Clean Energy Plan seeks “to make the American power sector ‘carbon pollution-free’ by 2035” among other “ambitious objectives” (Biden for President n.d.; McPherson-Smith 2020). “To achieve this, the plan carves out a role for greater nuclear power, offering reliable, emissions-free energy for consumers...but...omits how a Biden administration would manage the nuclear waste created in the process” (McPherson-Smith 2020). It does state that “Biden will support a research agenda through ARPA-C [Advanced Research Projects Agency for Carbon] to look at issues, ranging from cost to safety to waste disposal systems, that remain an ongoing challenge with nuclear power today” (Biden for President n.d.).

Most experts in the nuclear industry “agree that what’s needed is a permanent [commercial SNF disposal] site...that doesn’t need humans to manage it” (Brady 2019 Apr), in the interests of public safety and “intergenerational justice” (Schuppert 2011 May). However, in the absence of a federal permanent repository for commercial SNF after more than 60 years of effort,

“a quiet consensus has developed that for the near term, simply storing spent fuel while continuing to develop more permanent solutions is an attractive approach” (Bunn et al 2001 Jun, p. 8).

PROPOSED INTERIM CONSOLIDATED NUCLEAR WASTE STORAGE IN THE PERMIAN BASIN

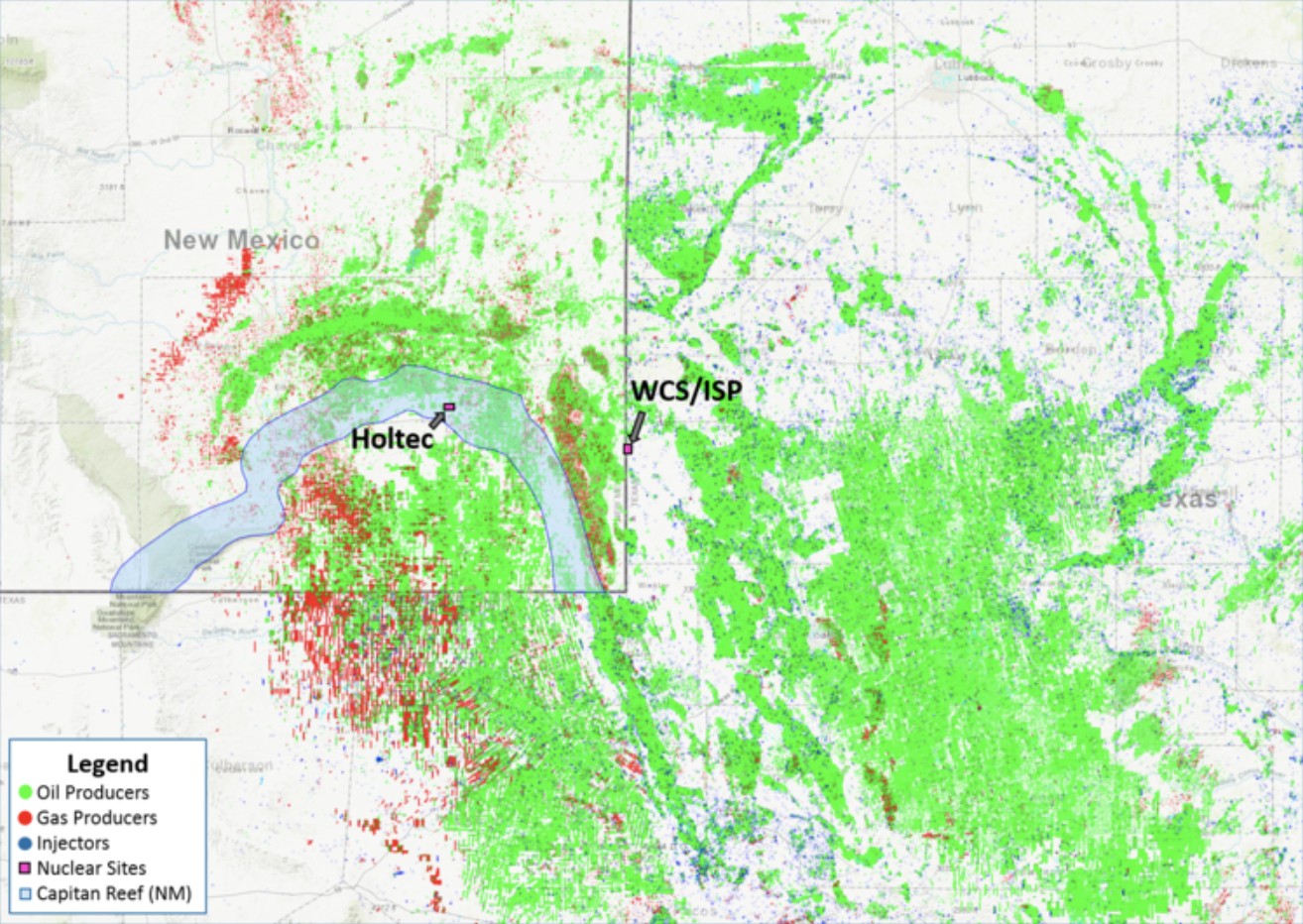

Amidst the Yucca Mountain rigmarole, in 2016 and 2017 two private entities—Holtec International and Waste Control Specialists—applied for NRC licenses to develop and operate interim consolidated SNF storage facilities in SE New Mexico and NW Texas, respectively (Holtec International 2017; Waste Control Specialists 2016).

The region in question, on Apache/Comanche/Jumano homelands and now known as the Permian Basin (Fig. 39), is “the biggest oil field in the United States” (Moore 2012; Rott 2019).

![]()

Figure 39. A map of the Permian Basin, on Apache/Comanche/Jumano homelands, with green indicating oil producers, red indicating gas producers, and arrows pointing to the two proposed consolidated storage sites. (Moore 2012; Protect the Basin 2020)

The approach concurs with the recommendation from a 2018 study from Stanford University “that the United States reset its nuclear waste program by moving responsibility away from the federal government and into the hands of an independent, nonprofit, utility-owned and-funded nuclear waste management organization” (Gabel Chui & Golden 2018).

In concept, a private company would manage a repository where SNF from across the country could be consolidated and stored in a safer environment than the power plant sites scattered nationwide (Fig. 40).

![]()

Figure 40. Illustration of a generic consolidated storage site. (Rott 2019)

Although considered to be “the most realistic approach for managing the tons of spent fuel” in the U.S., the proposed facilities are “held hostage to progress on Yucca Mountain” because “current law requires that the NRC issue a license for Yucca Mountain before a consolidated interim storage could begin to accept spent fuel” (Klaus 2020).

Experts in the nuclear industry generally agree that “simply put, the United States’ long-term repository for spent nuclear fuel is not going to be built at Yucca Mountain,” so some argue that we should officially abandon YMDGR, “move forward on consolidated storage for the next 40 to 50 years,” and identify a new site for a permanent repository through a “consent-based process” (Hamilton & Scowcroft 2012, p. 7; Stover 2012; Klaus 2020).

In a counterexample to community consent, local opposition to storing nuclear waste in the Permian Basin is well-encapsulated by a sign at the proposed site for Holtec’s consolidated interim storage facility in Lea County, NM, on Lipan Apache homelands, “on its side, uprooted from the ground and punctured with bullet holes” (Fig. 41) (Lea County Museum 2019; Rott 2019).

Figure 41. A sign at the proposed site for Holtec’s consolidated interim storage facility in Lea County, NM, on Lipan Apache homelands, “on its side, uprooted from the ground and punctured with bullet holes.” (Lea County Museum 2019; Rott 2019, courtesy of Nathan Rott/NPR)

The main concerns for SNF storage in the Permian Basin are potentially “catastrophic” economic disruptions, “real or perceived,” to the region’s oil and gas fields and “million-dollar agricultural interests” caused by the presence of a nuclear facility (Rott 2019).

In addition, states including Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas are wary of accepting nuclear waste from around the country because “existing federal laws treat radioactive waste a ‘privileged pollutant,’ exempting it from the regulatory authority of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and States” (Montoya Bryan 2019 Jun 27).

The 2012 Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Waste stated in its final report to the DOE that “experience in the United States

and in other nations suggests that any attempt to force a top-down, federally mandated solution over the objections of a state

or community—far from being more efficient—will take longer,

cost more, and have lower odds of ultimate success,”

(Hamilton & Scowcroft 2012, p. 9)

and by contrast, “consent and compensation” can effectively increase public reception to local nuclear waste storage

(Klaus 2020; Stover 2012), as seen in Finland, France, Spain, Sweden and the U.S. (Hamilton & Scowcroft 2012, p. 9).

The DOE’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) for transuranic (TRU) defense waste (Fig. 42) in Eddy County, NM, on Sioux/Cherokee/Iroquois homelands, is the “only deep geologic long-lived radioactive waste repository” in the United States (American Indian 2021). It was constructed in the 1980s and loaded with waste beginning in 1999 (Nuclear Waste Partnership LLC n.d.).

Figure 42. TRU defense waste generating sites and the storage site at the WIPP in SE New Mexico, on Sioux/Cherokee/Iroquois homelands. (American Indian 2021; State of Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects n.d.)

This successful nuclear waste shipping campaign demonstrates several important principles that should be applied to evaluate and develop future interim storage and permanent disposal sites, including “flexible and substantial” incentivization for volunteer communities, thorough logistical and transportation planning, and “transparency, accountability, and

meaningful consultation” with diverse stakeholders (Hamilton & Scowcroft 2012, p. 9, 13 & 15; Stover 2012).Regional planning near the power plant sites currently storing commercial SNF across the U.S. is also critical. In January 2019, the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act (NEIMA) began requiring the NRC “to submit a report to Congress identifying best practices for establishing and operating CABs [Community/Citizens’ Advisory Boards] to foster communication and information exchange between a [nuclear] decommissioning licensee and the local community” (Lincoln 2019).

HUMBOLDT BAY POWER PLANT CITIZENS ADVISORY BOARD

The NRC has utilized Community/Citizens’ Advisory Boards (CABs) since the 1990s to engage local communities with nuclear decommissioning projects (MacPherson 2019). Generally, CABs are “organized group[s] of citizens interested in safe decommissioning practices and spent fuel management” (Savage 2019). An NRC report to Congress from July 2020 offers seven recommendations for best establishing and operating CABs for nuclear decommissioning projects

(Radwaste Solutions Staff 2020).

The Humboldt Bay Power Plant Citizens’ Advisory Board (HBPP CAB) was established in 1998 and includes seats for community leaders, school principals, local elected officials, experts, local residents, and representatives from the state of California, PG&E, and environmental and community groups (MacPherson 2019; Waraich 2019).

While members say the HBPP CAB is “a good model for future boards” (Savage 2019) and praise PG&E for being “very receptive” to recommendations from the CAB while decommissioning HBPP Unit 3, there is “a real need to broaden the stakeholder base” of the HBPP CAB, with particular emphasis on tribal representation (Waraich 2019).

HBPP CAB members have also voiced desires for a more formalized educational framework (Savage 2019) and a way to keep the general public more informed, perhaps by giving CAB seats to the media or delegating at least one member to speak with the press (MacPherson 2019).

With NRC license termination of HBPP anticipated by the end of 2021 (Manetas 2020, p. 63; Talbott 2020 Sep), the HBPP CAB may turn its focus to the HB ISFSI.

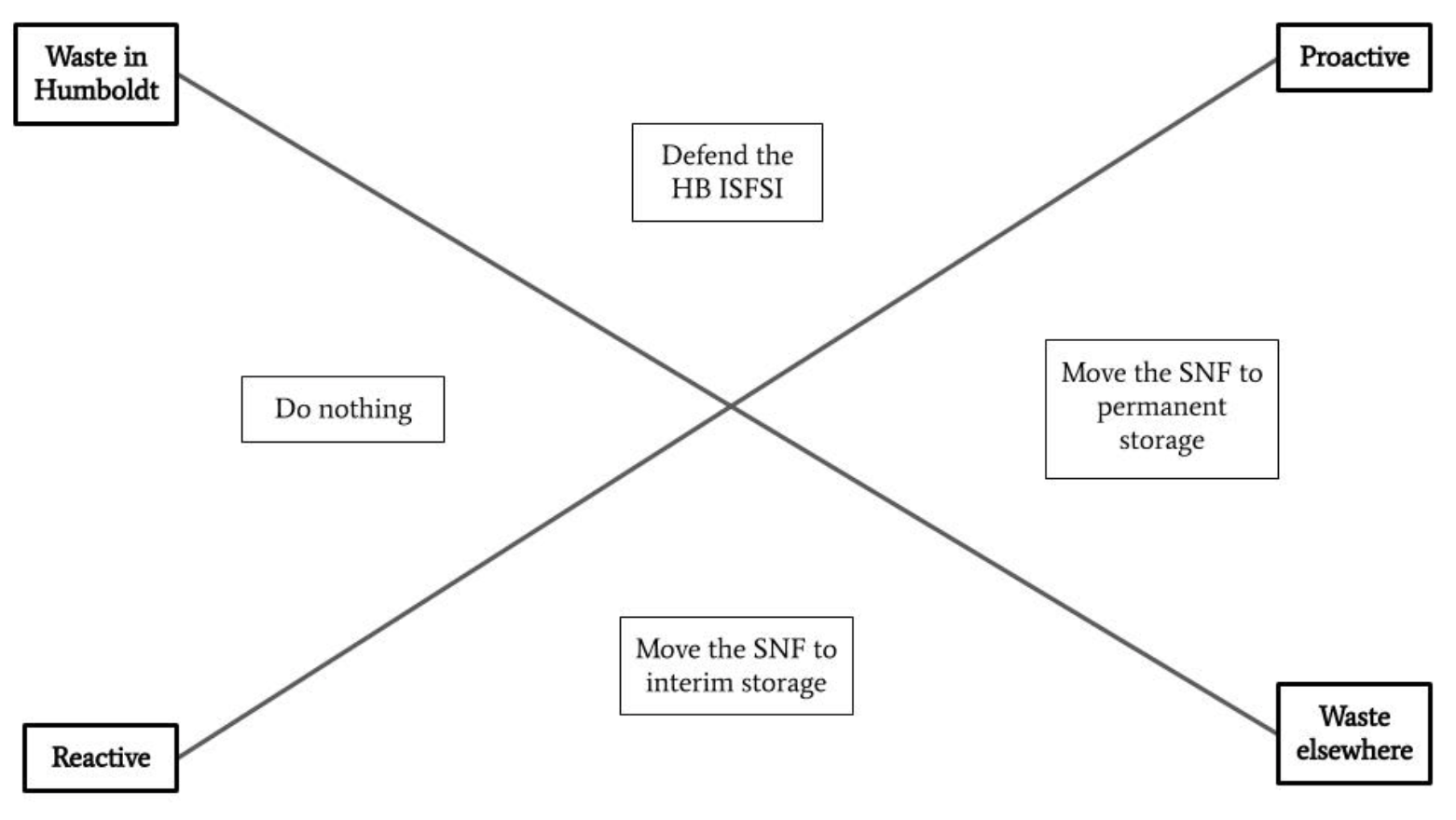

SCENARIO MATRIX OF POSSIBLE FUTURES FOR HUMBOLDT BAY’S COMMERCIAL NUCLEAR WASTE

To start developing a framework for future decision-making about nuclear waste management on Humboldt Bay (Wigi), we developed a very basic scenario matrix (Fig. 43) that lays out four possible futures for the commercial nuclear waste in the HB ISFSI, based on this literature review and compilation. However, long-term Humboldt Bay nuclear waste management will be far more complex that this bare-bones diagram suggests. It is important to actively manage Humboldt Bay’s nuclear waste on-site while simultaneously planning for different possibilities for off-site storage, as well as transportation between the two.

Figure 43. Scenario matrix of possible futures for Humboldt Bay SNF. (Marlow & Lowell 2020)

PATHWAYS APPROACHES TO RISK MANAGEMENT & PLANNING

PATHWAYS APPROACHES TO RISK MANAGEMENT & PLANNING

The “Pathways Approach,” also known as the “Managed Adaptive Approach” or “Adaptive Phased Management,” is a more complex and appropriate framework for developing a plan for long-term nuclear waste management on Humboldt Bay (Lowell 2021 Mar 30). The basic idea is that the choices we make know, as well as uncertain conditions (such as sea-level rise), will determine our options for decision-making in the future (Fig. 44) (Lowell 2021 Mar 30).

Figure 44. A flowchart showing “adaptation pathways that conceptualise the emergence of future routes for adaptation...Current time is located towards the left of the diagram. Dark arrows represent different possible routes that could be taken, circle arrows represent decision points, lighter arrows lead to maladaptive dead-ends, and dashed arrows represent more-or-less transformative pathway segments.” (Fazey et al 2015)

A PATHWAYS APPROACH TO NUCLEAR WASTE MANAGEMENT IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

A PATHWAYS APPROACH TO NUCLEAR WASTE MANAGEMENT IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

The San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) in Orange County, CA, on Acjachemen/Payomkawichum homelands (Native Land CA), offers a case study for applying a Pathways Approach to nuclear waste management. After Southern California Edison (SCE), similar to PG&E in Northern California, lost a lawsuit from environmental groups about its first plan to dispose of nuclear waste from SONGS on-site, SCE applied the Pathways Approach and published the Strategic Plan for the Relocation of Spent Nuclear Fuel from SONGS in 2021. The SONGS Strategic Plan explores alternative pathways for the long-term management and disposal of the nuclear waste currently stored at SONGS in Orange County, CA. The basic flowchart from the SONGS Strategic Plan (Fig. 45) can be directly applied to the HB ISFSI, but an “HB ISFSI Strategic Plan” would need to be site-specific.

Figure 45. A flowchart based on applying the Pathways Approach to nuclear waste management to SONGS that explores alternative pathways for the long-term managment and disposal of the nuclear waste currently stored at SONGS in Orange County, CA, on Acjachemen/Payomkawichum homelands. (Native Lands CA; San Onofre Community Engagement Panel 2021, 7:27)

Visual Timeline

Pre-19th c. to the present

The Wiyot people live on and steward the water and land in and around Wigi (Humboldt Bay), including Jurouk Higuchguk (Buhne Point) that are part of their ancestral territories on the California North Coast (Canter 2021 Mar, personal communication; Wiyot Tribe 2011).

1850

Captain Hans Henry Buhne (see image), the modern namesake for Buhne Point, sailed the Laura Virginia into Humboldt Bay in April 1850 (Find a Grave 2010; Rohde 2006).

1890s

The construction of jetties at the mouth of Humboldt Bay (see image)by the Army Corps of Engineers intensified wave action in the bay and accelerated erosion of Buhne Point (Laird 2019 Nov, p. 11; Page 2005; Walters 2013).

1950s

1950s

The Army Corps of Engineers built a protective rock seawall along the southeastern coast of Humboldt Bay, including Buhne Point, to buffer it from wave-induced erosion (see image)(Laird 2019 Nov, p. 11; Page 2005).

(Abigail Lowell 2020 Dec)

1958

The first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States, Shippingport Nuclear Power Station, began operating near the current site for Beaver Valley Nuclear Power Station in Beaver County, Pennsylvania (in red text on the left side of the map)

(American Society of Mechanical Engineers 2020; Craddock 2016).

Also, the Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) announced in the Humboldt Standard that it planned to build a new nuclear plant: Humboldt Bay Power Plant (HBPP) Unit 3 on Humboldt Bay, California at Buhne Point (Herbert et al 2012, p. 17).

1963

PG&E began operating Humboldt Bay Power Plant (HBPP) Unit 3, the 7th nuclear power plant in the United States (see image) (California Energy Commission 2020, p. 3; Herbert et al 2012, p. 28).

1976

After 13 years of operations, PG&E closed down HBPP Unit 3 for routine refueling and a seismic design retrofit in response to “new seismic information” about Southern Humboldt Bay

(see image)

(Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1).

Also, “the state of California placed a moratorium on the construction and licensing of new nuclear fission reactors until the federal government implements a solution to radioactive waste disposal” (California Energy Commission 2020,

p. 1).

1979

The Three Mile Island nuclear reactor located near Middletown, PA

(see image)

had a loss-of-coolant accident when the plant’s water pumps failed and the normally-circulating water required to absorb heat from the nuclear reactor evaporated as steam. When the water level in the reactor vessel dropped, the nuclear core overheated and partially melted down. (Fortin 2019; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2018 Jun)

Luckily, despite damage to the reactor, scientific monitoring showed that the radioactivity release “had negligible effects on the physical health of individuals or the environment” (U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2018 Jun).

Nevertheless, the accident generated public fear and distrust “fueled, in part, by the sense that people weren’t getting enough information about what had happened—and what they should do to stay safe” (Fortin 2019).

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) introduced new safety regulations following the accident (Fortin 2019; Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2018 Jun).

1982

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act mandated the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)

(see image)

to take ownership and possession of all commercial SNF in the U.S. and permanently dispose of it by the year 1998 (Coplan 2008 May, p. 20; Manetas 2019 Oct; World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar).

1983

Although the 1976 HBPP Unit 3 shutdown was originally intended to be temporary, PG&E determined “that the cost of completing the required upgrades would make it uneconomical to restart the unit” and announced plans to decommission Unit 3 (see image) (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1).

1987

Amendments to the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 designated Yucca Mountain, Nevada as the site for the U.S. federal deep geologic repository (see image) (Coplan 2008 May, p. 20; Manetas 2019 Oct; World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar).

The proposed Yucca Mountain Deep Geologic Repository (YMDGR) would exist in a mined repository 984 feet (300 meters) underground “in an unsaturated layer of welded volcanic tuff rock.” For nuclear waste containment, it would rely on “the long-term durability of engineered barriers” and the site’s “extremely low water table,” which lies nearly 1970 feet (600 meters) beneath the surface. (World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar).

1988

The NRC approved PG&E’s decommissioning plan for HBPP Unit 3 and revised its operating license to a possess-but-not-operate license (SAFSTOR status) set to expire in 2015 (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 40; Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2013, p. 1). PG&E designed and implemented an on-site spent fuel pool (SFP) at HBPP to begin meeting its decommissioning requirements (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 4).

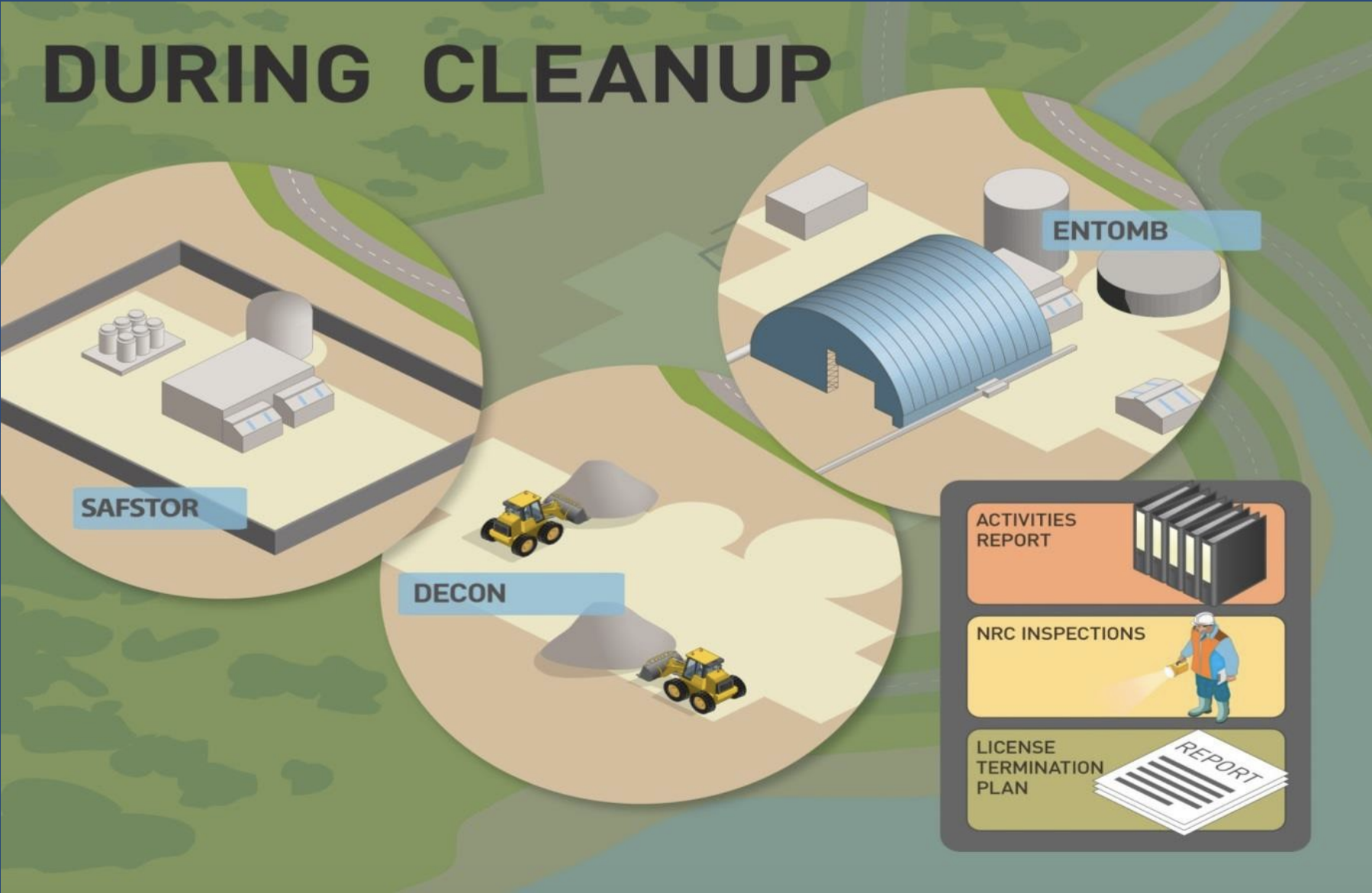

The NRC permits decommissioning nuclear power plants in 3 ways: DECON, ENTOMB and SAFSTOR (see image)

(Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 33).

DECON initiates “immediate dismantlement” of the plant. ENTOMB allows nuclear utilities to “encase radioactive contaminants in a structurally sound material like concrete” until they decay adequately. SAFSTOR, as was applied at HBPP Unit 3, ensures nuclear plants are “maintained and monitored in a condition that allows radioactivity to decay” until safe, and then fully decommissioned. (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 33)

1989

The DOE announced that “technical and institutional complexities of site characterization make it unlikely that a repository [at Yucca Mountain] would be available before 2010” (see image) (Dunster 2017-2018).

1990s

PG&E worked with the energy technology company Holtec International to develop the Holtec International Storage, Transport and Repository System for Humboldt Bay (HI-STAR HB) (see image), an on-site dry cask storage system for the SNF from HBPP Unit 3.

2004

PG&E announced that three nuclear fuel rods, or about four pounds of uranium, were unaccounted for at HBPP “due to conflicting records of their location” (California Energy Commission 2020, p. 4; Nuclear Threat Initiative 2004; Sacramento Business Journal 2005). The fuel rods were never officially recovered

(California Energy Commission 2020, p. 4), but an interim report from PG&E to the NRC after months of searching (see image) “detailed ‘reasonable, but not conclusive, evidence’ that deteriorated fragments recovered from the bottom of a used-fuel storage pool [SFP] at the defunct plant in fact were the remains of the missing fuel rods” (Hall 2005;

Sacramento Business Journal 2005).

2005

The NRC issued PG&E a site-specific license to implement the HI-STAR HB at the HB ISFSI on Buhne Point and operate it for 20 years until 2025 (see image) (Benner 2005, p. 1; Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2017 Nov, p. 16).

2007

The Humboldt Bay Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installation (HB ISFSI) and its associated infrastructure was constructed adjacent to PG&E’s partially-decommissioned HBPP on Buhne Point (Ch2m Hill Engineers 2015, p. 16), encompassing slightly more than 11,000 square feet (see image) (Compas & Maniery 2003, p. 6).

2008

Six casks, or overpacks, of nuclear waste from HBPP Unit 3 were moved from wet storage in SFPs into dry storage in the underground HB ISFSI on Buhne Point, where they remain to this day. Five casks contain SNF and the sixth contains other highly-level, Greater Than Class C (GTCC) waste

(see image).

(Ch2m Hill Engineers 2015, p. 16)

(Ch2m Hill Engineers 2015, p. 16)

2010

The Obama administration tried to eliminate funding and “withdraw the [NRC] license application” for the proposed YMDGR (see image) (Mascaro 2010).

2011

A partial nuclear reactor meltdown and some off-site release of radiation resulted from an earthquake and tsunami off the northeast coast of Japan that flooded the coastal Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (see image) (Chen 2019 Sep; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2019 Aug).

2013

The U.S. Court of Appeals ordered the NRC to resume reviewing the DOE’s license application for YMDGR (see image), so the process continued (World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar).

2016

The NRC’s final safety evaluation report, final technical safety review and final supplement to the DOE’s Environmental Impact Statement for YMDGR all “established that the repository design would prove safe for one million years”

(see image)

(World Nuclear Association 2020 Mar).

The Trump administration’s 2017 budget proposal “included $120 million for the resumption of the license review for the repository at Yucca Mountain,” but Congress did not provide the funding (U.S. Government Accountability Office n.d.).

Waste Control Specialists, LLC applied for an NRC license to develop and operate an interim consolidated SNF storage facility in the Permian Basin in Northwest Texas (Waste Control Specialists 2016).

2017

The Trump administration’s 2018 budget proposal “included $120 million for the resumption of the license review for the repository at Yucca Mountain,” but Congress again did not provide the funding (U.S. Government Accountability Office n.d.).

Holtec International applied for an NRC license to develop and operate an interim consolidated SNF storage facility in the Permian Basin in Southeast New Mexico (see image) (Holtec International 2017).

2019

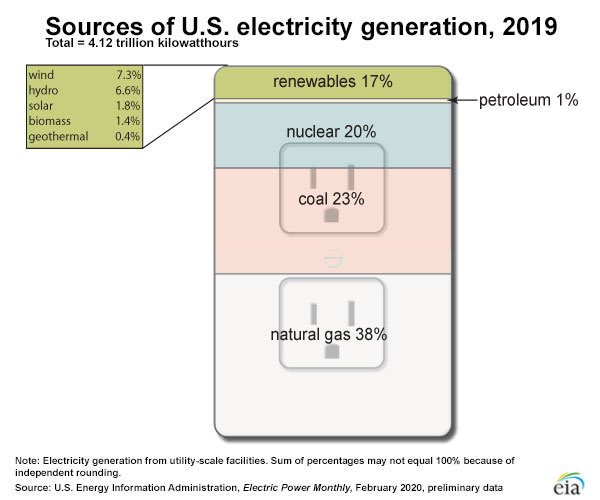

Sixty years since the first commercial nuclear power plant began operating in the United States, nuclear energy was the third-largest national source of electricity at 20%, behind only natural gas (38%) and coal (23%) (see image) (U.S. Energy Information Administration 2020 Mar).

The Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act (NEIMA) began requiring the NRC “to submit a report to Congress identifying best practices for establishing and operating CABs [Citizens Advisory Boards] to foster communication and information exchange between a [nuclear] decommissioning licensee and the local community” (Lincoln 2019).

PG&E plans that the DOE will transfer the SNF away from HB ISFSI between 2031 and 2033 (Welsch 2019, p. 32).

2020

In February, the Trump administration’s 2021 budget proposal did “not include funding for licensing of Yucca Mountain as a nuclear waste repository,” marking “an abrupt reversal of [the] administration’s policy” after three years of officially supporting the project (Hulac 2020). President Trump also tweeted his opposition to Yucca Mountain (see top image) (Trump 2020).

Then-presidential candidate Joe Biden (see bottom image) expressed his disapproval for the contradiction between Trump’s funding allowances for YMDGR and his “empty promises on Twitter” (Gartner 2020; Grandoni 2020). He emphasized that “under a Biden administration there would be absolutely zero dumping of nuclear waste in Nevada” (Gartner 2020; Grandoni 2020).

In June, the NRC extended PG&E's operating license for the HB ISFSI, originally set to expire after 20 years in 2025, for 40 additional years until 2065 (Welsch 2019 Mar, p. 34; Talbott 2020 Jun).

Decommissioning HBPP is in its final stages; PG&E prepared and submitted Final Status Survey Reports to the NRC, (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2020) and anticipates the NRC will terminate their HBPP operating license in 2022. (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2018, p. 16-17).

Then-presidential candidate Joe Biden (see bottom image) expressed his disapproval for the contradiction between Trump’s funding allowances for YMDGR and his “empty promises on Twitter” (Gartner 2020; Grandoni 2020). He emphasized that “under a Biden administration there would be absolutely zero dumping of nuclear waste in Nevada” (Gartner 2020; Grandoni 2020).

In June, the NRC extended PG&E's operating license for the HB ISFSI, originally set to expire after 20 years in 2025, for 40 additional years until 2065 (Welsch 2019 Mar, p. 34; Talbott 2020 Jun).

Decommissioning HBPP is in its final stages; PG&E prepared and submitted Final Status Survey Reports to the NRC, (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2020) and anticipates the NRC will terminate their HBPP operating license in 2022. (Pacific Gas & Electric Company 2018, p. 16-17).

![(13) Despite its legal obligation to provide permanent storage for all commercial SNF in the U.S. by 1998, the DOE announced in 1989 that “technical and institutional complexities of site characterization make it unlikely that a repository [at Yucca Mountain] would be available before 2010.” In particular, the decision was a response to concerns from State of Nevada researchers that an earthquake or volcanic eruption at Yucca Mountain could raise the groundwater table beneath the repository, flood the repository from below, degrade the dry casks and leak radioactive waste into the environment. For nuclear utilities storing commercial SNF on-site at decommissioned power plants, such as PG&E, this announcement effectively delayed the promise of federal acceptance and disposal by at least 12 years. (Dunster 2017-2018; Krotz 2002; State of Nevada Nuclear Waste Project Office 1999; U.S. Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board 2017, p. 1)](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/29420741bb13ad801b193af7f718804c9b3d191e5df9489f7e6ffd10ff196e70/Yucca_cutaway.jpg)